On January 7, 2025, plastic surgeon Dr. Elisabeth Potter posted a video claiming that UnitedHealthcare called her mid-surgery to justify an inpatient stay for a breast cancer patient receiving reconstructive surgery.

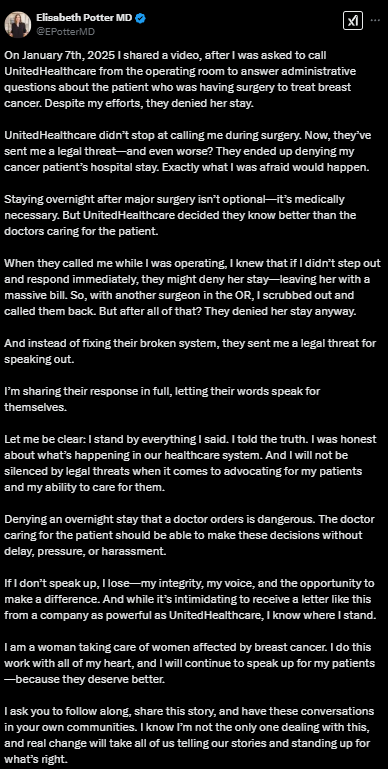

Dr. Potter posted on X.com:

On January 13th, counsel for United Healthcare sent Dr. Potter an unpleasant letter. “Re: Your Defamatory TikTok and Instagram Videos About UnitedHealthcare.” Counsel is Clare Locke, the firm hired by Dominion to sue Fox. Fox settled for almost $800 million. I’m assuming that sum is larger than Dr. Potter’s nest egg.

United Healthcare demanded the record be corrected, the videos removed, a public apology posted, and the doctor condemn the threats of violence against UnitedHealthcare populated in the comments feed. They also “expected [her] to contact Newsweek and any other media outlet who ha[d] reported on the issue and inform them that [her] claims were false, that [she] unequivocally retract [her] claims, and that [she] request them to remove all stories about [her claims].”

Dr. Potter posted that legal letter online.

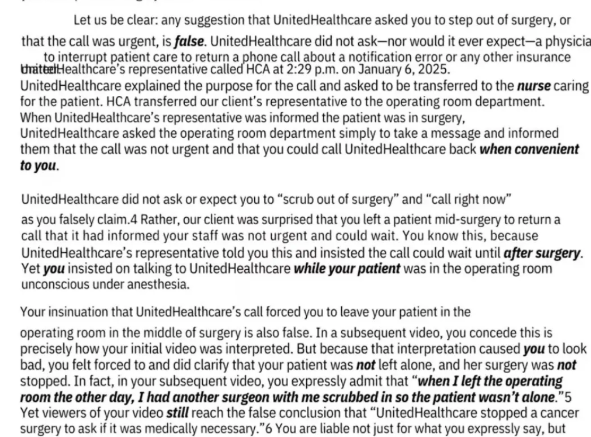

The letter noted that UnitedHealthcare never asked the good doctor to step outside of the operating room. Apparently, there was some confusion as to whether the patient would be observed overnight or admitted. Such issues crop up regularly.

From the posted letter:

What is clear is that physicians spend a LOT of time advocating for their patients to get necessary treatment. Likely, Dr. Potter did not want to perform the surgery only to inform her patient that she can’t spend the night. She likely did not want to freak her patient out. A good doctor would not want to freak their patient out. The larger point in her videos is that physicians spend a lot of time doing bureaucratic work to advocate for their patients’ care. This eats into time that could be spent, well, caring for their patients. Whether this was a misunderstanding or not is not my point. The letter’s implication was that Dr. Potter was at risk of being sued if she didn’t comply with UnitedHealthcare’s demand.

My take. UnitedHealthcare should settle down. I do not believe its reputation was harmed in any way by Dr. Potter’s video posts. She was highlighting a matter of public concern. If she came to an erroneous conclusion, it was not intentional or reckless disregard for the truth, which is what UnitedHealthcare would need to demonstrate in such a matter of public concern. Further, did her posts eat into UnitedHealthcare’s bottom line? I doubt it. Actually, that was facetious. The answer is “No.”

When UnitedHealthcare’s CEO was assassinated, I had understood that he was trying to improve its processes to be more doctor-friendly. And more patient friendly. If true, his untimely demise was even more of a shame. Meanwhile, sending threatening letters to a surgeon advocating for her patient does not improve UnitedHealthcare’s reputation. On the contrary, it tarnishes it.

If UnitedHealthcare has some tips to help Dr. Potter’s patients going forward, then by all means, help her. Her job is hard enough. But cease and desist with the cease and desist threats.

Entirely unrelated to the Potter/UnitedHealthcare saga, we’ve been asked, Can someone or an entity with a tarnished reputation even sue for defamation? This leads to an analysis of the “libel proof doctrine.”

The doctrine has developed along two pathways. The first—the “issue-specific” approach—bars relief for a plaintiff whose reputation related to a specific subject matter is so tarnished that he or she cannot be further injured by allegedly false statements on the matter. The second— the “incremental harm” doctrine—bars relief where the challenged statements harm a plaintiff’s reputation far less than unchallenged statements in the same article or broadcast….

Under the issue-specific approach, plaintiffs with notorious past criminal behavior are the most likely to be found libel-proof, particularly when the allegedly defamatory statements relate to criminal conduct. For example, a Texas Court of Appeals found a plaintiff libel-proof as to allegedly false statements that he was a methamphetamine dealer and leader of a burglary ring where his criminal record spanned twenty-five years and showed two drug convictions and six convictions for burglary and theft. Likewise, a Tennessee Court of Appeals found a plaintiff libel-proof related to a report that he was suspected of committing additional crimes, including murder, where the plaintiff had already been convicted of multiple violent felonies.

Importantly, the issue-specific doctrine is not limited to plaintiffs with criminal records, but can also apply to a plaintiff complaining of libelous statements in a solely civil or professional context. A Michigan Court of Appeals, for example, dismissed a defamation suit brought by Jack Kevorkian, finding that Kevorkian was libel-proof because his celebrity and reputation as a well-known proponent of assisted suicide meant that the effect of “more people calling him either a murderer or a saint is de minimis.” And the Second Circuit found that a plaintiff was libel-proof as to the subject of adultery because magazine and newspaper articles, as well as the plaintiff’s own testimony, showed wide dissemination of the information that the plaintiff was living with another woman while still married.

The incremental harm doctrine holds that if the defamatory statement does no more harm than the true statements about the plaintiff, then there is no actionable claim for defamation. The incremental harm doctrine has been discussed and embraced by the Seventh Circuit in cases such as Haynes v. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. where the court famously wrote that “falsehoods which do no incremental damage to the plaintiff’s reputation do not injure the only interest that the law of defamation protects.”

What is inarguable is that most, if not all, health insurance companies in the US have a reputation problem. I don’t have a solution for it. It’s hard to see how a physician commenting about a specific carrier faux pas, even if inaccurate, tarnishes what is already a battered reputation.

Finally, I think United Healthcare picked on the wrong doctor.

Sometimes legal fights escalate and David slays Goliath. As in the case of North Face Apparel Corp. versus The South Butt, LLC. North Face is known as the giant apparel company focused on the rugged outdoorsman.

The company sold products with the tag line, “Never Stop Relaxing,” a parody of The North Face line, “Never Stop Exploring.” A wavelike pattern and the company name appear near the upper right or left shoulder on jackets and shirts, similar to the logo and placement used by The North Face.

The North Face, a division of VF Corp, sued. The lawsuit sought unspecified damages and asked the court to prohibit The South Butt from making, marketing and selling its line of fleeces, T-shirts and shorts.

At issue was the question of parody or piracy. The lawsuit claimed The South Butt marketed apparel that “infringes and dilutes The North Face’s famous trademarks and duplicates The North Face’s trade dress in its iconic Denali jacket,” referring to a popular fleece jacket marketed by the company.

“While defendants may try to legitimize their piracy under the banner of parody, their own conduct belies that claim,” the suit said, noting that The South Butt had twice attempted to obtain a U.S. trademark registration.

In a whimsical response Watkins [the attorney] wrote that “the consuming public is well aware of the difference between a face and a butt …”

The case settled.

The court ordered mediation in the case, and on April 1, 2010, the parties reached a closed settlement agreement.

South Butt should have pocketed their winnings and declared victory. But they didn’t.

Two days later, Winkelmann Sr. formed a company called “Why Climb Mountains” which sold “The Butt Face” products. In October 2012, the Winkelmanns admitted in court that they violated the settlement agreement with The North Face. In addition, the court ordered them to abandon a trademark registration application for The Butt Face, shut down their web store and Facebook page, surrender all merchandise, and pay $65,000, an amount that would be reduced by $1,000 for every month of compliance.

You got to know when to hold them and know when to fold them.

What do you think?

Physicians advocating on the part of their patients against insurance companies should be immune from suit. Insurance companies have grown wealthy by charging higher and higher premiums, while paying only a fraction of what the actual charge is. They also tend to follow what Medicare pays, though medicare collects far lower premiums. Have the books every been opened on what they collect and what they pay out? Year over year, it seems that the health insurers make more money. We continue to see patients harmed by insurance companies that are practicing medicine by telling patients what is and is not reimbursable, and thus available to them for healthcare. Every physician has seen this if they have been in practice for any length of time.

Many years ago, I had a cancer patient that was dying, and I could not get the medical director to speak to me on the phone. I was on hold for 3 hours. He left without speaking to me. The patient needed additional pain medicationss. I could not get them authorized. We pay for insurance to cover large sums that might occasionally be necessary for medical treatment. Let us also be clear that the government through legislation has also completely distorted the health insurance market, and caused costs to rise dramatically.

In my experience covering 25 years, regarding State Medical Boards, absolutely no consideration is made as to the character of the person who makes a complaint against a physician or surgeon. It absolutely makes no difference if the complainer is a known drug dealer or worse or the “Queen of England”.

That is my observation and it sickens me.

Richard B Willner

The Center for Peer Review Justice

Much is made of the high cost of medical care by Government, and of course the “blame” is directed against doctors. At least that is how Congress has looked at it. It is no secret that billions of dollars are spent by insurance companies to lobby Congress. Some of it may be a good thing: For example, life insurance companies created certain tax havens for people who purchase insurance products. These are utterly artificial. But they do benefit insurance purchasers.

Since the end of WWII, Europe has not paid for its self-defense against Russia. US tax payers paid for it. Finally, it looks like they have been forced to pay for slightly more. Over the years, this allowed Europe to provide a “socialist base” to their populations. Naturally they could afford to do this. We paid the bill to protect them. Their armies are tiny. Their defense budgets microscopic.

U.S. Health insurance companies have a horrible reputation. We personally have United Healthcare, the most expensive Medicare Supplement they have. We personally have not faced challenges from them. US taxpayers and UHC pay for a very expensive orphan drug for my wife. (Thank you, BTW).

My understanding is that the new Bill signed by the President has some “changes” that force American healthcare insurance to make some changes to benefit US Citizens. I hope they are meaningful.

Unfortunately, I have no miracles to offer US taxpayers in their perennial battles against healthare insurers. I’m hoping reduction of some Governmental waste will reduce our taxes. Most physicians, even retired ones, still pay lots of taxes. And their patients pay a great deal for health insurance and their Medicare insurance supplement products. Yes, and we pay for Medicare too. Physicians actually know that healthcare is never “free.”

Real American citizens pay a lot for goods and services that other countries offer for quasi-free. It’s past time for them to pay up for themselves. The graft taken by Democrats for their various Leftist pretensions has been astronomical. We’re hoping for some reductions in that hemorrhage.

Michael M. Rosenblatt, DPM

I wasn’t aware that we were discussing politics. The insurance industry is well known for not giving “a hoot” about their insureds. As long as their CEOs can line their pockets. And they do practice medicine without a license. There is another small issue – that of their outsourcing their provider “hotlines”. When we call, for instance, MetLife to get patient information we are usually routed to the Philippines. (We have heard family conversations and roosters and chickens in the background.) MetLife still uses patients’ social security numbers for the majority of the ID numbers. So patients’ PHI is being put out there with little protection. That, in itself, is a bigger problem than political disparagement.