When I was a resident, one attending asserted he’d rather have a resident at bedside making the evaluation than Harvey Cushing (the father of neurosurgery) at home.

Technology has improved and, today, diagnoses can often be made remotely.

Still, when a nurse beckons, and says she’s worried, you should listen. A recent paper supports that assertion.

The title is self-explanatory: The fifth vital sign? Nurse worry predicts inpatient deterioration within 24 hours.

The article concluded that nurses’ pattern recognition and sense of worry provides important information for detecting acute physiologic deterioration.

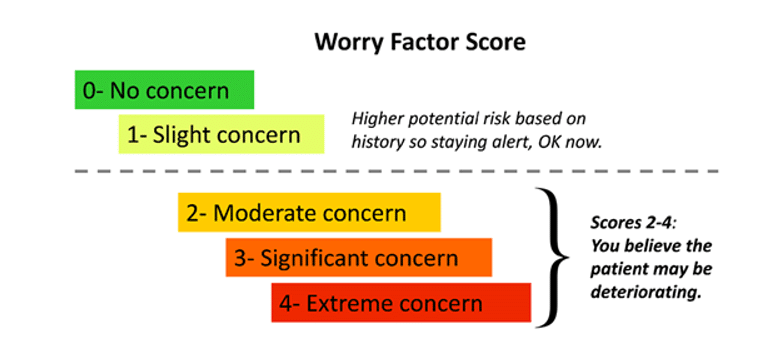

The study focused on a single tertiary care academic hospital that had high standards for hiring registered nurses. The researchers recorded nurses’ perception of patient potential for deterioration on two medical and two surgical hospital units. The scoring was simple. A score of zero was no worry at all. A score of four was “five alarm” worry. [Five alarm on 0-4 scale should remind readers of an analogous scale in the movie Spinal Tap.] More broadly, a score of 2-4 suggested the nurse believed the patient may be deteriorating.

Nurses filled out a form for their sense of worry at the beginning of each shift for each of their patients. They updated their number if their perception changed.

Nurses collected whether they notified the provider to come to the bedside, and whether the provider showed up to evaluate the patient.

Highly experienced charge nurses were also asked to independently record their predictions for a subset of patients.

The collected data was evaluated by three reviewers. A physician of the same specialty to which the patient was hospitalized – but otherwise had no contact with the patient. An experienced nurse who had no contact with the patient. And a physician, nurse, or NP who had no contact with the patient.

How did our Nostradamuses do for 3,000+ patients?

Pretty good.

Nurses recorded calling the provider (usually a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or resident)—either to inform them of the patient’s status or to request them to come assess the patient—a total of 1314 times, and recorded the provider coming to the patient’s bedside due to patient deterioration 686 times. The number of potential deterioration events identified by nurses was 492. Additionally, there were 169 outcome events in total (86 RRT (Rapid Response Team) calls, 76 transfers to the ICU, and 7 codes).

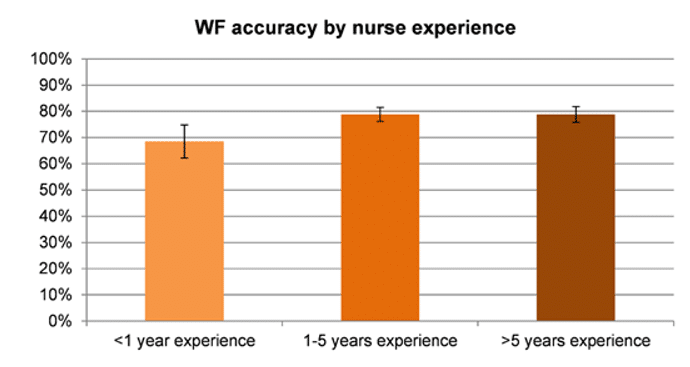

Of the 492 potential deterioration events identified by nurses, 380 (77%) were confirmed by reviewers. Reviewer confirmation rates by nurses’ years of experience varied. Nurses with less than 1 year of experience had a significantly lower accuracy rate compared to nurses with more than 1 year of experience (68% vs 79%, P = 0.04).

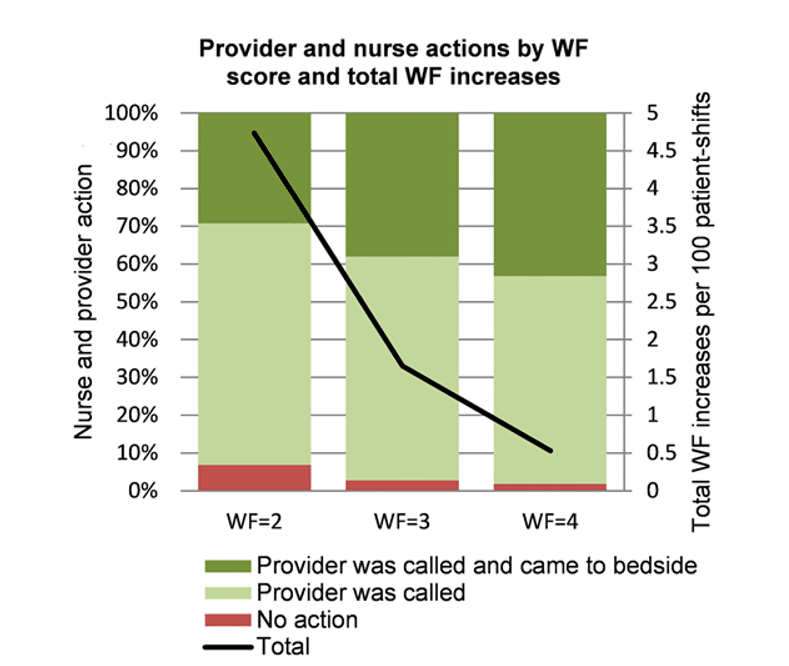

Physicians came to bedside in proportion to the nurses’ worry.

When the WF was 2, nurses called the provider in 93% of cases, and providers assessed the patient at the bedside in 29% of cases;

These proportions increased to 97% and 38%, respectively, for a WF of 3; and to 98% and 43%, respectively, for a WF of 4.

The probability of an RRT call taking place in the following 24 hours was 16% after a WF of 2 or above, 37% following a WF of 3 or above, and 63% following a WF of 4.

The authors concluded that nurses’ judgement captured through this simple score is predictive of inpatient deterioration: 77% of the potential deterioration events identified by nurses were confirmed by an independent set of reviewers, and a patient with a WF of 3 or more is 40 times more likely to require ICU transfer in the next 24 hours (likelihood ratio = 40.4). This suggests that the nursing staff’s sense of worry, whether through analytical skills or through pattern recognition, is very accurate in identifying deteriorating patients and should be more consistently valued and utilized, considering incorporation into the medical record.

Is the study applicable to all hospitals? Maybe. Maybe not.

Data collection was conducted in a single tertiary referral center that hires carefully selected and highly trained registered nurses. The accuracy of these WF scores could change if conducted in a different center, where nurses might have different skillsets.

In other words, not all nurses in all settings are equal. And even in this study, more experienced nurses were more accurate in predicting patient deterioration.

If the worry factor is included in the electronic medical records, physicians would be well advised to be aware of that score. A WF score of 4 with no physician response -after being notified- will not help the patient or the potential legal defense.

And even with lower scores that still are associated with “worry”, some type of physician response – even if only a written analysis as to why the patient is likely stable and does not need hands-on evaluation – would be better than staying isolated in your medical record lane.

We encourage our members to contact us anytime they sense trouble. We provide solutions. And we’ve honed our own “worry score” since 2001. Countless member physicians have avoided trouble as a result.

Discover the benefits of membership by examining our protection plans. And when you’re done, examine the featured articles below. They dispense salient advice any practice can apply.

Perfect Patient Dismissal & Termination Letters

Respond Masterfully to Negative Patient Reviews

Discover the Regulatory Landmines Most Doctors Miss

So, my former attending in neurosurgery might now add:

He’d rather have a resident or worried nurse at bedside making an evaluation than Harvey Cushing (the father of neurosurgery) at home.

What do you think? Click here to leave a comment and join the conversation below.

Jeffrey Segal, MD, JD

Chief Executive Officer and Founder

Dr. Segal was a practicing neurosurgeon for approximately ten years, during which time he also played an active role as a participant on various state-sanctioned medical review panels designed to decrease the incidence of meritless medical malpractice cases.

Dr. Segal holds a M.D. from Baylor College of Medicine, where he also completed a neurosurgical residency. Dr. Segal served as a Spinal Surgery Fellow at The University of South Florida Medical School. He is a member of Phi Beta Kappa as well as the AOA Medical Honor Society. Dr. Segal received his B.A. from the University of Texas and graduated with a J.D. from Concord Law School with highest honors.

In 2000, he co-founded and served as CEO of DarPharma, Inc, a biotechnology company in Chapel Hill, NC, focused on the discovery and development of first-of-class pharmaceuticals for neuropsychiatric disorders.

Dr. Segal is also a partner at Byrd Adatto, a national business and health care law firm. With decades of combined experience in serving doctors, dentists, and other providers, Byrd Adatto has a national pedigree to address most legal issues that arise in the business and practice of medicine.

Many hospitals have a fairly stable core of nurses, even though there is always turnover. As we get to know the nursing staff, it becomes evident that they do know about their patients. After all, they spend far more time with the patients than we do when we make AM & PM rounds. In over 40 years of practice as a urologist, I found that listening to the nurses concerns was always valid, even if someone overstated the case or made an error. It was at the very least an opportunity for teaching. I firmly believe that I would rather have made one extra trip, even in the middle of the night, than miss an important change.

I am far more concerned about the nurses who fail to recognize obvious problems, or fail to report them because they did not want to be chewed out by the doctor. For example, I had a patient who had classic symptoms of a PE that were ignored for lack of understanding by the nurse of what was happening.

I used to teach the residents the tag line from the old TV show from the 1960’s…”1 Adam 12, 1 Adam 12, see the man”.

As I was taught and then passed down, if a nurse is calling you at 3AM more than likely it is for something important. But the nurses assessment is only as good as her education and training allowed. IF the patient is to have the benefit of your knowledge and experience then you must get out of bed to see the patient. Otherwise you are substituting her knowledge and experience for your own.

The more painful times are when the nurses don’t call you.

And they should have.

An apocryphal story heard decades ago on a planet far far away….

Physician walks onto the floor and hears, beep beep beep in the distance as the alarm sound of a pulse oximeter.

He rounds the corner and the beeping gets louder.

He passes the nurses station and the beeping gets louder.

He gets to just outside of the patient room and the beeping of the pulse oximeter alarm is very insistent.

He goes inside. The patient is a male in his early 50s that had prostate surgery the day before.

The oxygen saturation is 81%.

The patient relates that the darn beeping kept him up all night.

The physician listens to the patient’s lungs and the patient is in florid pulmonary edema.

The physician steps away from the bedside to speak to the nurse.

The nurse relates that she had called the surgeon the night before because of the desaturation and he had ordered a breathing treatment for the patient.

The physician said, why did you not call the surgeon again or call me when the saturation did not improve.

The nurses response, well I did something about it, I called the surgeon.

20mgm of Lasix IV and an hour later the patient’s saturation was back to 98%.

The epidural morphine the patient had for pain relief the day before was not the presumptive cause of the patient’s oxygen desaturation.

Moral of the story is to always see the patient.

When I was in medical school (in the early 70’s), our clinical interactions were primarily with interns and residents, very rarely with attendings. Turns out that nurses were a particularly valuable source of practical education. They might not know a lot about the detailed underpinnings of what goes on in a diseased body, but they harbored a wealth of useful info about what to do when encountering one. I always paid attention.

And…the sixth vital sign should be a patient who wants to write notes to his or her family before surgery or while in an ICU.

I have idea how people know they’re about to die, but it’s uncanny how often this is the case. Twice, I ignored a patient having “a bad feeling” before surgery. “Bad feelings”? We’re scientists, not astrologers. Both patients had very poor outcomes.

I never again ignored that, nor did I ignore when ~I~ had a bad feeling about an operation. It happened rarely, but it happened. It’s amazing how creative you can become when you’re scared. Using these two simple, if totally arcane tools, I was blessed with an enviably low complication rate. Not zero, but much lower than many of my colleagues’. Obviously, this means nothing if a patient is crashing—it’s for elective cases.

I’ve included this phenomenon in lectures I’ve given. Others needed to hear this: it gave them permission to adopt the practice themselves. When you’re starting a new specialty, you are, by definition, outside the box. Whenever a possibly predictive tool came along, I used it.

Our residency chairman used to say to us – “A call from the ER is a call to see the patient”. I also learned that if you listened to senior nurses’ concerns while taking call, you learned a lot. Thank you.