Dr. Hassan A. Saad is an orthopaedic surgeon practicing in Michigan. This physician shares the same first and last name as another physician, who worked in the same city. This other Dr. Hassan has a different middle initial. His middle initial is “T” and opposed to our protagonist, whose middle initial is “I”.

What a coincidence.

Dr. Middle Initial “T” Saad was convicted of federal opioid-related charges. See ECF No. 10-2, PageID.132 (Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs, order suspending medical license of Hussein Toufic Saad, M.D.).

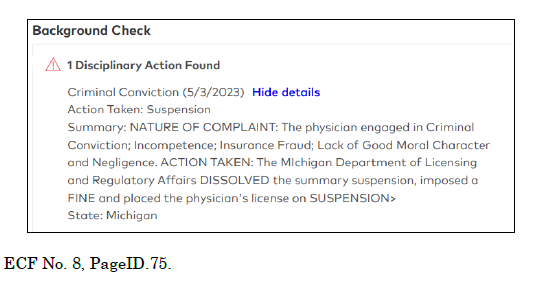

Dr. Middle Initial “I” Saad received a “bad boy” badge on his Healthgrades profile.

Oops.

Saad alleges that at least one of his patients saw this on the Healthgrades site; that patient presented this excerpt to Dr. Saad’s office and said that she had “looked up his name” on Healthgrades and learned that Dr. Saad “had a criminal conviction” and that “his licensed was suspended.” ECF No. 8, PageID.74.

Upon information and belief, Plaintiff alleges “several patients of Plaintiff have reported to being turned appalled by the information published by Defendants, and therefore refused to be seen by Plaintiff for medical treatment into the future in light of the disparaging, defamatory statements made by the Defendants.” ECF No. 8, PageID.79.

Healthgrades said it was a case of mistaken identity. Same first name. Same last name. Same practice community.

Dr. Middle Initial “I” Saad alleged that Healthgrades was negligent in publishing the incorrect story. Dr. Middle Initial “I” Saad noted he does indeed have a different middle name. And, no less important, the two Saads have different NPI numbers.

The lawsuit alleged: defamation; intentional infliction of emotional distress; and tortious interference with a business relationship or expectancy.

Healthgrades filed a Motion to Dismiss. This is an early action in a trial. In a Motion to Dismiss,

The complaint must provide

“‘a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief,’ in order to ‘give the defendant fair notice of what the . . . claim is and the grounds upon which it rests.’” Moreover, the complaint must “contain[] sufficient factual matter, accepted as true, to state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face.”

In other words, the facts, as alleged, must support the specific legal breach and remedy requested.

Here, the court gave sustained life to two of the three claims. The following claims survived: defamation and tortious interference with a business relationship or expectancy. This claim perished: intentional infliction of emotional distress.

Regarding defamation, Healthgrades argued that it had a qualified privilege to speak on a matter of public interest, even if it made an error.

Defendants assert that “[u]nder Michigan law, communications are protected by a qualified privilege (even if false) if they are made in furtherance of a duty to a third-party or the public welfare.” ECF No. 10, PageID.103. “Qualified privilege ‘extends to all communications made bona fide upon any subject-matter in which the party communicating has an interest, or in reference to which he has a duty to a person having a corresponding interest or duty.’” Id. (quoting Timmis v. Bennett, 352 Mich. 355, 366 (1958)). Because Defendants are speaking on a matter of public concern or under a duty to a third party, under their interpretation, Saad must plead (and eventually prove) actual malice rather than negligence.

Qualified privilege, if allowed, would set the bar higher, making it harder for Dr. Saad to prevail. In the legal world, malice doesn’t mean ill intent. The defendant might actually have ill intent. But that doesn’t matter. What matters is whether the mistake was based on reckless disregard for the truth. More than just an innocent mistake.

But the analysis does not stop here.

The Michigan Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized the general rule that a defamation defendant is not entitled to a qualified privilege in a case involving a private-figure plaintiff, even if the private-figure plaintiff was defamed in the course of a discussion of an issue of public concern.

Here, Dr. Saad is a private-figure plaintiff. He’s not a celebrity or a politician. His use of the media was/is limited.

The Michigan Legislature codified this standard in 1988, statutorily providing that defamation of a private figure requires only a showing of negligence, not actual malice. Mich. Comp. Laws § 600.2911(7); J & J Constr. Co., 468 Mich. at 734.

There have been limited exceptions to this application of qualified privilege. (To reiterate, if qualified privilege IS allowed as a defense, the defamed plaintiff has more to prove. It’s harder for the defamed plaintiff to prevail and collect a check.)

This is not to say that limited exceptions for a qualified privilege were gone completely, despite any doubt that Rouch might have cast on qualified privileges in general. See id. at 201 (“[I]t is obvious that the policy imperatives that led to the adoption of many of the qualified privileges, including the public-interest privilege, resulted from the then-existing harshness of the law of libel and the absence of any constitutionally based privilege. As described above, that harshness has been removed.”). Some of the qualified privileges that predated Rouch survive today, especially in the employment context. For example, in the 1970s the Michigan Court of Appeals held that security officers at a grocery store could ask a cashier, who they suspected of stealing $5, where she had put the money in front of other employees. See, e.g., Tumbarella v. The Kroger Co., 85 Mich App 482, 494 (1978) (“[A]n employer has the qualified privilege to defame an employee by publishing statements to other employees whose duties interest them in the same subject matter.”). And post-Rouch, an employer could similarly ask its employees which one of them stole money, therefore implying one of them was a thief. See Smith v. Fergan, 181 Mich. App. 594, 598 (1989). An employer can also still enjoy a qualified privilege to defame a plaintiff by telling prospective employers that a plaintiff was discharged for dishonest behavior. See Gonyea v. Motor Parts Fed. Credit Union, 192 Mich. App. 74, 79 (1991) (“[A]n employer has a qualified privilege to divulge information regarding a former employee to a prospective employer.”).

So, if there’s a pre-existing duty, for example, such as for an employee needing to report mischief to an employer, and the scope of disclosure is narrow and limited, the defamed individual will have a harder time winning their case. The key is that the publication must be limited.

But however [Healthgrades] tries to cast that case as being simply about the ability to make defamatory comments about a physician, the qualified privilege analysis in that case again relies on the limited nature of the publication to specific parties pursuant to a duty to those parties…. Thus the cases [Healthgrades] cite as the best proof of their proposed qualified privilege (Ryniewicz, Prysak, Another Step Forward, and Lefrock) are instead better understood as applications of an (admittedly not always well-defined) rule that defamation defendants have a qualified privilege for limited-purpose statements made pursuant to a duty to a limited audience, tailored to the necessity of the publication and the duty in question. None of these cases are like the case here.

Finally, Healthgrades argued that only a limited number of people saw its error. These were people specifically searching for Dr. Saad. While Healthgrades sends information to the online world at large, only a scant few would have come across the error; namely, those searching for a Dr. Saad in a specific town.

The court concluded that if it accepted Healthgrades defense,

that logic would become the exception that swallows the rule: granting digital publishers a shield of privilege when they put information freely available online, as long as they plausibly assert a shared interest with, and a duty to, their readers and viewers. Michigan law does not support that interpretation.

This is not the end of the case. Nor the beginning of the end. This case has just started. And no matter the outcome, it can and likely will be appealed. The take home message at this stage is this: Online libraries of information need to exercise caution when publishing their own content.

Be aware that many of the protections granted to online publishers for “user generated content” through Section 230 probably do not apply here. For the moment, this comes down to publication of first party versus third party content.

Many physicians might say that only Google matters. They’ll say “Healthgrades is not important”

We disagree. Healthgrades is important.

First, Google ranks physicians based on what it “sees” on other sites such as Healthgrades. A strong signal on Healthgrades is a strong signal to Google. Next, patients do look at Healthgrades to confirm or verify credentials such as Board of Medicine actions or criminal history. If Healthgrades was irrelevant, then Dr. Saad might not even have a case. The court has ruled otherwise for the moment.

How can a physician easily check their profile on a site like Healthgrades? Easy. Join Medical Justice. It’s one of the first things we investigate.

What do you think?

Digital errors that are egregious and made because of an incompetent act which cause harm are a form of defamation. Rest assured that some patients saw the post, but words of this kind spread through our community and it would not be surprising that some physicians knew about it as well. Healthgrades needs to pay up, be it, a reasonable amount.

I would think that HealthGrades should also be compelled to print, in bold, a correction that all of Dr. Saad’s patients, past, present and future, should be able to see. And a public apology might be nice.