America locks up a lot of people. Approximately 2 million people are incarcerated. Also, many people have interactions with law enforcement, and they may be arrested and placed in jail pending trial.

These people also get sick.

What type of care are these individuals entitled to?

I was made aware of this issue during a meeting of the American College of Legal Medicine. Shout out to Christopher Meredith, MD, JD for an excellent presentation highlighting the complexity.

The New England Journal of Medicine published an article on this topic.

Let’s go over some basics.

If an officer sees a person having an MI on the street, he generally owes no direct duty of care. It’s possible, even likely, he would render care. Or call for assistance. But in most states, the law does not impose an affirmative duty to “help a drowning victim.” You probably would not invite such a non-helper to dinner. There are exceptions for rendering aid – for example, lifeguards do need to help the drowning victim. And fireman do need to make reasonable efforts to help a person evacuate from a burning building.

And if an officer stops an individual to ask questions, again, there’s generally no duty to render anything other than first-aid. If the person who is stopped is free to leave, they are not “arrested.” And there’s no additional duty of care.

“Aside from the rights and duties secured by the U.S. Constitution, lawmakers have not sought to enact statutory protections that guarantee immediate access to medical care during law-enforcement interactions. Thus, in all U.S. jurisdictions we have reviewed, except Connecticut, officers are not statutorily required to immediately summon care when they observe that a person is experiencing a medical crisis or when a person communicates that they are in medical crisis. Apart from the legal duty to render first aid, or to summon care in a narrow set of circumstances, such as when a person is injured, officers are generally governed by policy rather than by statute in deciding whether to grant access to emergency medical services.”

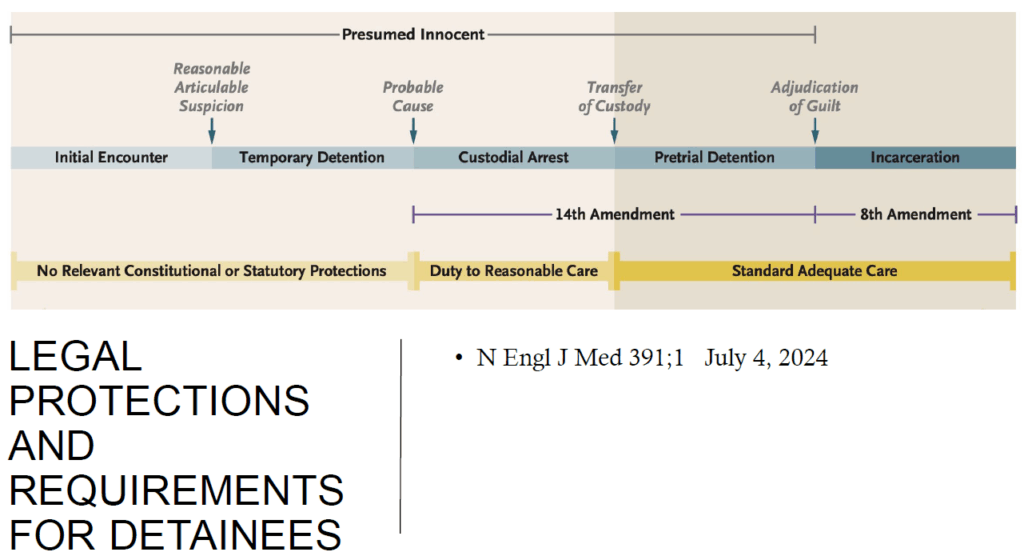

Once a person is not free to leave, that is treated as a custodial arrest. The individual is presumed innocent under the law. At arrest, the system mandates a duty to provide “reasonable care.” This is guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.

This individual may be charged formally (indicted), and the 14th Amendment still guides, but if there’s a custodial detention, that individual will only be entitled to “standard adequate care.” Once convicted, and incarcerated, the 8th Amendment takes over, but the standard remains – “standard adequate care.”

What does this mean?

For post-conviction inmates, the 8th Amendment applies and protects against “Cruel and Unusual punishment.”

In the context of medical care, this means the system/provider cannot engage in willful indifference to inmate’s condition(s).

Willful indifference means “treatment must be so grossly incompetent, inadequate, or excessive as to shock the conscience or to be intolerable to fundamental fairness.” For example: deliberately ignoring the express orders of an incarcerated person’s physician

Negligence and medical malpractice are not sufficient to establish “deliberate indifference.”

The willful indifference standard in prison medical care originated in the seminal case, Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976). This was a claim based on federal law – 42 U.S.C. §1983.

Plaintiff asserted cruel and unusual punishment for inadequate treatment of back injury while engaged in prison work. The trial court dismissed the case for failure to state a claim.

At appeal, the Court reversed: “deliberate indifference” by prison personnel to a prisoner’s serious illness or injury constitutes cruel and unusual punishment, contravening the Eighth Amendment.

The opinion in Estelle versus Gamble concluded the plaintiff must prove deliberate indifference – an elevated standard beyond mere negligence.

The opinion cited an earlier case, Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947), where the Court concluded it was not unconstitutional to force a prisoner to undergo a second effort to electrocute him after a mechanical malfunction thwarted the first attempt.

This conclusion does not mean, however, that every claim by a prisoner that he has not received adequate medical treatment states a violation of the Eighth Amendment. An accident, although it may produce added anguish, is not on that basis alone to be characterized as wanton infliction of unnecessary pain. In Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947), for example, the Court concluded that it was not unconstitutional to force a prisoner to undergo a second effort to electrocute him after a mechanical malfunction had thwarted the first attempt.

The willful indifference standard is a heavy lift.

There are other laws which apply.

The Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) is a law that limits prisoners’ ability to sue the government over prison conditions. The PLRA was passed in 1995 as part of Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America”.

Goals of the PLRA

- Reduce frivolous lawsuits

- Give corrections officials the ability to fix problems before litigation

- Lighten the caseload for courts handling prisoner litigation

How the PLRA works

- Requires prisoners to exhaust all available administrative remedies before filing a lawsuit

- Requires prisoners to pay court filing fees in full. inmates must pay filing fees in full, with no option for a fee waiver.

- Limits attorneys’ fees. Attorney’s fees are capped so often need pro bono services – in short supply. Inmates who represent themselves prevail a mere. 6% of the time.

- Limits damages

- Makes it harder to obtain prison and jail population caps

PLRA permits correctional facility defendants to request termination of court orders regarding their facility conditions after 2 years – even if not all terms have been met. This requires a new lawsuit to address recurring violations.

OK, let’s tackle a real world dilemma. If a prisoner has Hepatitis C (HCV), are they entitled to curative treatment with glecaprevir-pibrentasvir or sofosbuvir-velpatasvir? These medications are not cheap.

In the United States, the prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is much higher in correctional settings as compared to the general community. Between 2011 and 2012, estimates based on 12 state prisons in the United States showed an HCV seroprevalence of 9.6% to 41.1% More recent estimates based on surveys of all state prison systems in the United States conducted in 2019-2023, paired with publicly available data, suggest that 15.2% of the United States prison population is HCV antibody-positive and 8.7% viremic. Regardless of which data is examined, the HCV prevalence in prisons is markedly higher than in the overall United States population, which has an estimated prevalence of current HCV infection of 0.9%. In addition, when considering the movement of individuals in and out of the correctional system during a 1-year period, it is estimated that approximately 30% of all individuals living with HCV infection in the United States pass through a correctional system in a given year.

Prisons prioritize.

“Although treatment should ideally be considered for all inmates with HCV, in the correctional setting, medical necessity often dictates whom to treat first, with medical necessity usually determined by the degree of liver fibrosis or by the presence of significant HCV-related extrahepatic manifestations. Many state prison systems have used the Bureau of Prisons 2021 HCV Clinical Guidance or a similar protocol to guide prioritization for HCV treatment. This guidance specifically lists the following conditions to be high risk for disease progression and complications, thus requiring more urgent consideration for treatment:

Advanced hepatic fibrosis or known cirrhosis

Liver transplant recipients

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

Comorbid conditions associated with HCV, including cryoglobulinemia, certain lymphomas or hematologic malignancies, or porphyria cutanea tarda Immunosuppressant medications Evidence for progressive fibrosis, including stage 2 fibrosis on liver biopsy

Select comorbid conditions associated with faster progression of fibrosis, including HIV, HBV, other comorbid liver diseases, diabetes mellitus

Chronic kidney disease

Persons born between 1945 and 1965

Persons already on HCV treatment, including those newly incarcerated.”Despite the high cost of therapy, correctional systems have a constitutional obligation to provide access to medical care. Nevertheless, it has been difficult to precisely define what this means with regard to treatment of HCV infection. Regardless of the prioritized order in which persons in correctional facilities are treated, there are / have been several class-action lawsuits challenging the blanket restriction of treatment of persons with little to no fibrosis in whom treatment is deemed not medically necessary.

In summary, the 8th amendment protections for the carceral population provide only minimal inmate protection because of the very high bar of willful indifference. The PLRA of 1996 currently makes prisoner recourse extremely difficult, expensive, and provides only short-term, narrowly tailored remedies. There are no national standards for healthcare in prisons.

What do you think?

In a strange turn of events, I was involved as an expert witness in a case involving a “privately owned prison.” Not being an attorney, I am and was not familiar with the legal issues of treatment for Government vs. private prison ownership. I don’t know what the differences are, if any.

The case I was involved in demonstrate severe patient contributory negligence. So much so that his poor circulation resulted in amputation, the proximate result of both failure to treat properly and patient contributory negligence. I won’t go into the details, for privacy reasons and I am not aware of any requirements regarding disclosure.

Suffice to say that plaintiff’s attorney was “satisfied” with my expert witness testimony. Medical Justice reported a circumstance requiring very expensive therapy for incarcerated individuals. We all know that medical/surgical care can be enormously expensive and we all wonder what and why we owe incarcerated people the very high standard of care (some) would experience on the outside.

Podiatry care is unusual in the incarcerated community. It is therefore not surprising that amputations could occur failing this standard of care. Or even make them worse. Not all people who treat lower extremity conditions are “aware” of the implications of circulatory collapse in the leg and foot.

So, in the final analysis, my case was a situation where the standard of care was not met, whatever that is for incarcerated people. There are no answers to this vexing problem. We are struggling now to provide care for millions of undocumented “visitors” to this Country, courtesy of our previously open borders. The open borders were a direct result of the fear of that particular ruling party to risk losing Congresional seats.

Medical/surgical care is never free, even if it is so advertised, in order to get votes. Someone still has to pay for the educational requirements of those who provide it. It is not like “just printing more money.”

Michael M. Rosenblatt, DPM

That was the situation

Mike,

I know that case extremely well. In fact, I was the one who suggested to the attorney to hire you. This was an “impossible” case. No question. There are specific details that I will not discuss. But, I will state that your Experts report was 28 pages. It was, “creative”. Absolutely outstanding.

The opposing attorney who has an outstanding track record told the plantiff’s attorney that he calls you “Rosenblatt The Genus”.

You have been retired for many decades. You are certainly not a professional expert. Period.

I have hired experts for 25 years and I have never seen a result like the one that you were part of.

I am familiar with section 1983 cases to the extent that I know that I do not know enough. But, our group has gotten respectable settlements. I am very grateful for that as I know how difficult litigation is.

Richard B Willner

The Center for Peer Review Justice

http://www.PeerReviewJustice.ORG

When I was in practice I had to treat many prisoners from the nearby federal prison. They were receiving care for all kinds of different surgical needs. The shacking was an issue. The guard outside of the operating room was an issue. Under normal circumstances firearms are not permitted in hospitals.

Care of inmates in prisons? I would suggest that if Medicaid covers the treatment, then it should be offered to prisoners. With perhaps one broad exception, which is transgender reassignment surgery. That is elective surgery and should not, in my opinion, be covered at taxpayer expense while someone is in prison, or not.

What about if someone is on death row for 10 years awaiting the appeals process? Should long term sustaining care be provided? I’d suggest, reluctantly that the answer is yes.

We may not wish to provide care to some heinous prisoners. But our ethics would dictate that in or out of prison such patients are entitled to our professional care.

Would Nazi’s on trial at Nuremberg be entitled to competent medical care? Yes, as much as it pains us to do so. Even knowing that their death sentence is the likely outcome of the trial.

Taking care of patients with swastika tattoos may be repugnant, but we are still obligated to provide such care regardless of the patient’s views or actions.