We have previously written about medico-legal challenges related to brain death determination.

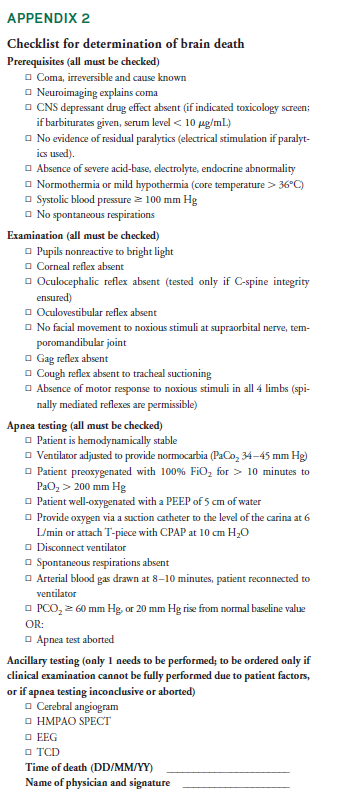

The American Academy of Neurology updated its guidelines in 2010 to create more uniform determination. Its checklist is as below.

There’s a checklist related to systemic information (eg: the patient is in a coma, systolic blood pressure or body temperature are not abnormally low). There’s a checklist related to the neurological examination (identifying an absence of all brainstem reflexes). There’s a checklist related to apnea testing.

With apnea testing, the patient is removed from ventilator support to see if rising CO2 levels in the blood will stimulate the medulla to initiate spontaneous respirations. The test lasts up to 8 minutes. If the patient starts breathing, the test demonstrates at least some brainstem function. If the patient has no spontaneous ventilation after 8 minutes, the test adds evidence to diagnosis of brain death.

Eight minutes without ventilation can be problematic in it of itself. In a retrospective study of 63 patients who had the test performed, 5% of patients experienced mild hypoxemia (without any consequences); 17% experienced mild hypotension (easily managed with vasopressors). 98% of patients were able to complete the test. That one patient desaturated and the test was aborted. For many patients on whom the test is conducted, most are determined to be dead. On those where the test is not conclusive, the risk of harm appears to be low.

Here’s one hurdle.

In some states, the family must provide consent for the doctor to perform the apnea test. And the family might not be open to the idea of declaring a loved one dead; even if all evidence points in that direction.1

In Montana, in 2016, a 6-year-old boy drowned. The traditional tests to ascertain brain death were performed. The tests showed no brain function and the clinical team strongly suspected brain death. They wanted to administer an apnea test and the mother objected. The hospital filed a legal motion to allow the test to be performed. The court ruled in favor of the mother in September 2017. It held the mother has the sole legal authority to make medical decisions on behalf of her son, including the decision as to whether any future brain functionality examinations should be performed.

The court held that (a) Montana Uniform Determination of Death Act does not mandate that providers conduct a brain death examination, nor specifically grant the legal right to conduct a brain death examination. (b) Next, an individual’s right to choose or refuse medical treatment including whether or not to conduct a brain death examination is protected under the Montana Constitution. (c) Finally, there was no compelling state interest to override the mother’s federally protected right to make medical decisions on behalf of her child.

In December 2016, the patient was transferred home where he continued to be supported.

Other states have the same requirement. In 2006, in Kansas, a young boy drowned. His parents refused to consent to an apnea test. The court issued an injunction prohibiting the medical center from performing a “brain viability exam.” The child was transferred home six weeks later.

In contrast, two other states, Virginia and Nevada, do NOT require familial consent for an apnea test.

In Virginia, a lower court ruled a medical center could perform the apnea test over the family’s objections. The family appealed to the Virginia Supreme Court and asked for an expedited appeal. The Supreme Court refused. To speed up the process While waiting for the case to be briefed, the patient died based on cardiopulmonary criteria. This judicial decision is not binding on future outcomes, the main argument that was being promoted by the medical center was clarified; namely, the apnea test is not “health care” requiring consent.

In Nevada, the legislature took control of the issue. Its amended Uniform Determination of Death Act which took effect in October 2017 stated:

A determination of the [brain] death of a person…is a clinical decision that does not require the consent of the person’s authorized representative or the family member with the authority to consent or withhold consent.

In some states, determination of brain death can put doctors in a catch-22 situation. Declaration of death falls within the domain of health care providers. Using American Academy of Neurology guidelines to make that determination, physicians must perform an apnea test. If the state mandates familial consent is required to perform that test, and the family refuses, then the determination of brain death cannot be made.

What do you think? Weigh in using the comments box below. And if you haven’t already, subscribe to our newsletter for weekly content.

Typical here in the United States. The Apnea test is the one test that is the most difficult to perform in the context of true brain death. I do not see where the parents’ have the right to block this part of the exam. In lieu of this I think an angiogram should then be required to confirm no blood flow to the brain and brain stem.

There was a recent story in the news about a 13 year old boy that was in a coma and his parents had already signed papers for his organs to be harvested. Then he woke up, shortly before they were to being organ harvest.

This is an area of medicine where the physicians damn well better get this right.

Three successive EEGs showing brain death should be the standard, not minimal or equivocal activity. None. With no sedative of other drugs given.

Apnea by itself is not conclusive. As I understand it early on with brain injury apnea is common but becomes less so over time as the brain heals.

The parents have the right to determine medical care for their child unless it is going to cause proven harm to the child, ie not treating a cancer, etc. Medical authorities no matter how well meaning do not have this right under our constitution. In addition this decision must be divorced from the ability to pay, which underlies some of these issues.

Operating principal should be “if you pay the piper, you get to call the tune.”

Seems that the state has an interest–and standing, should it come to court–if it is the payer for future care. If the family (or other entity not getting state funding) is going to assume care, then they should get to make the call.

I’m afraid I must disagree with “retired” on the “ability to pay issue.” That underlies the whole argument. The state is not obligated to pay for after-death care.

These cases are so sad, I’m glad I’m not a neurologist.