In 2017, a high profile medical malpractice highlighted what is euphemistically known as “overlapping surgery.”

Before plodding ahead, let’s get our terms straight.

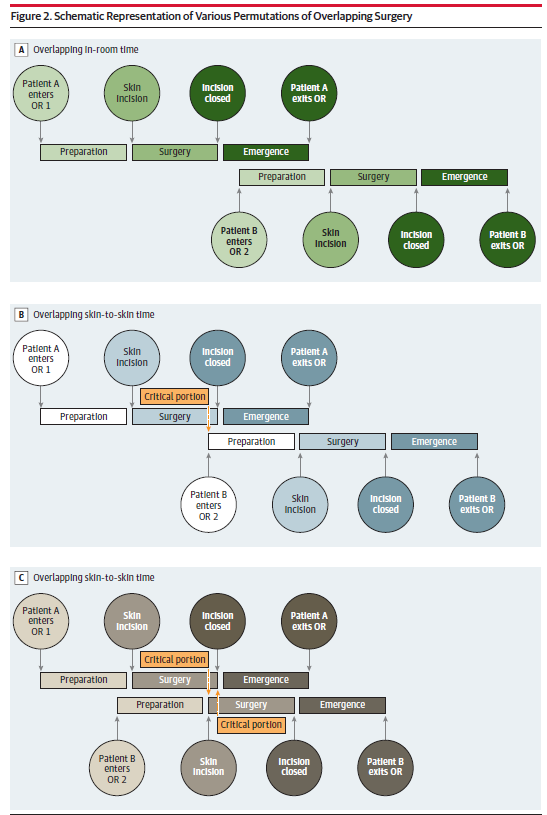

The American College of Surgeons defines operations as concurrent “when the critical or key components of the procedures for which the primary attending surgeon is responsible are occurring all or in part at the same time” and as overlapping “when the key or critical elements of the first operation have been completed, and … a second operation is started in another operating room while a qualified practitioner performs noncritical components of the first operation.

With concurrent surgery, the “hard part” of the two surgeries are done at the same time.

With overlapping surgery, the “hard part” of the two surgeries are NOT done at the same time.

And, even with overlapping surgeries, distinctions are made as to how much overlap is actually occurring.

This issue has been addressed by Senate Finance Committee and has been a hot topic in medical centers where high volume surgeons engage the practice. In 2016, the American College of Surgeons updated its Statement of Principles:

Concurrent or Simultaneous Operations

Concurrent or simultaneous operations occur when the critical or key components of the procedures for which the primary attending surgeon is responsible are occurring all or in part at the same time. The critical or key components of an operation are determined by the primary attending surgeon. A primary attending surgeon’s involvement in concurrent or simultaneous surgeries on two different patients in two different rooms is inappropriate.

Overlapping Operations

Overlap of two distinct operations by the primary attending surgeon occurs in two general circumstances.

The first and most common scenario is when the key or critical elements of the first operation have been completed, and there is no reasonable expectation that the primary attending surgeon will need to return to that operation. In this circumstance, a second operation is started in another operating room while a qualified practitioner performs noncritical components of the first operation—for example, wound closure—allowing the primary surgeon to initiate the second operation. In this situation, a qualified practitioner must be physically present in the operating room of the first operation.

The second and less common scenario is when the key or critical elements of the first operation have been completed and the primary attending surgeon is performing key or critical portions of a second operation in another room. In this scenario, the primary attending surgeon must assign immediate availability in the first operating room to another attending surgeon.

The patient needs to be informed in either of these circumstances. The performance of overlapping procedures should not negatively affect the seamless and timely flow of either procedure.

The American College of Surgeons states that concurrent surgeries are not appropriate (and this parallels Medicare billing rules); while overlapping surgeries are, as long as the patient is informed.

A recent paper looked at retrospective data to see whether overlapping neurosurgical procedures put any patients at increased risk. Data from matched overlapping to non-overlapping procedures were analyzed. The primary differences between the two groups were narrow. The overlapping surgery patients had longer in-room times and longer skin-to-skin times; possibly because the team was waiting for the surgeon to show up and do the critical work. Regardless, there was no association between mortality, morbidity, or worsened functional status. In aggregate, overlapping procedures did not put the patient in harm’s way.

The primary argument in favor of overlapping surgeries is that is has the potential to benefit patients by maximizing efficiency and making highly sought-after specialists available to greater number of patients. And recent data suggests this benefit is not at the expense of increased patient risk.

What do you think?

Ten years ago, we ran a contest, encouraging doctors to reveal if they had been involved in a frivolous lawsuit. We awarded a prize to the Most Frivolous Lawsuit. Cold comfort. Still, the winner did receive a free membership for one year with Medical Justice. We are running that same contest again.

Send us a brief description of what you believe qualifies for the most frivolous lawsuit. Email us at infonews@medicaljustice-staging.shfpvdx8-liquidwebsites.com. You have to have personal knowledge of the case. Either you were a named defendant. Or you knew the named defendant.

The winner will receive a free year’s membership to Medical Justice. Determination will be made by December 14, 2018 and announced soon after via our weekly e-blast and blog.

(The usual caveat, void where prohibited by law).

May the best defendant win.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeffrey Segal, MD, JD

Dr. Jeffrey Segal, Chief Executive Officer and Founder of Medical Justice, is a board-certified neurosurgeon. In the process of conceiving, funding, developing, and growing Medical Justice, Dr. Segal has established himself as one of the country’s leading authorities on medical malpractice issues, counterclaims, and internet-based assaults on reputation.

Dr. Segal holds a M.D. from Baylor College of Medicine, where he also completed a neurosurgical residency. Dr. Segal served as a Spinal Surgery Fellow at The University of South Florida Medical School. He is a member of Phi Beta Kappa as well as the AOA Medical Honor Society. Dr. Segal received his B.A. from the University of Texas and graduated with a J.D. from Concord Law School with highest honors.

If you have a medico-legal question, write to Medical Justice at infonews@medicaljustice-staging.shfpvdx8-liquidwebsites.com.

Supposedly there isn’t increased risk with overlapping surgeries. Apparently data has not shown increased risk. However, I think we all know full well that even the non critical portion of a surgery is quite likely to be performed better by th the primary surgeon than by others such as house staff, surgical assistants or techs, etc. In other words, maybe the risk is not demonstrably higher (although I am certain it is at least a little bit higher), but the quality of the wound closure, or the dissection, or the approach to name a few examples, is not as good as when carried out by the main surgeon most of the time. To suggest otherwise is a bit self-serving and not entirely honest.

The primary reason for these overlapping surgeries is to make more money for the surgeon and or the facility. It is not demonstrably safer for the patient. There is the risk of extended anesthesia time for the following surgery if there is a complication delaying the ending of the preceding procedure.