Each year, there are over 100 million emergency department visits in the US. Imaging is performed in over 50% of such encounters. CT scans are performed in 20% of such visits.

Not infrequently, a surprise finding is identified.

It is estimated that an actionable incidental finding (AIF), defined as a “mass or lesion, detected by an imaging examination performed for an unrelated reason” for which follow-up is recommended, will occur in 5% to 30% of imaging studies and nearly one-third of CT examinations1 2 3. A recent meta-analysis revealed a pooled prevalence of 31.3% for any incidental finding on ED CT studies 4. Among potential tumors, the majority of these findings are benign, but some represent precancerous lesions or early-stage cancers that offer an opportunity for earlier diagnosis and treatment with potential reductions in morbidity and mortality5.

The emergency department is not an ideal place for transmitting the information to the patient about their actionable incidental finding (AIF).

The emergency department is busy. Priority is given to solving the acute problem. Many times, such problems are life threatening. If you don’t solve the life-threatening problem, the AIF will merely be academic.

Many patients in the ED have no primary care doctor for follow-up. Or they are instructed to locate follow-up, but opt against it.

If a patient is admitted, there may be multiple physicians caring for the patient. Who is supposed to take charge of the AIF?

And, if the patient is provided information about their incidentaloma, aren’t they responsible for seeking follow-up?

In 2023, best practices were published in the Journal of the American College of Radiology to address this thicket.

A 15-member panel was formed, nominated by the ACR and American College of Emergency Physicians, to represent radiologists, emergency physicians, patients, and those involved in health care systems and quality.

The panel identified four areas: (1) report elements and structure, (2) communication of findings with patients, (3) communication of findings with clinicians, and (4) follow-up and tracking systems. A survey was constructed to seek consensus and was anonymously administered in two rounds, with a prior agreement requiring at least 80% consensus.

The first challenge was identifying what would be in the radiologist’s report, and where.

There was strong consensus (93%-100%) in the first round of the survey regarding elements that should be included in the overall report, including the presence of an AIF; lesion size, location, and characteristics; follow-up modality and time frame; evidence supporting recommendations if available; documentation of any notification or communication; and patient-facing language.

There was also strong consensus in the first round of the survey (87% “agree to strongly agree”) that AIFs should be reported in a structured or templated format.

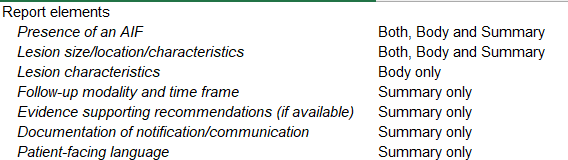

In terms of where these elements would be included, the body or summary of the report, the consensus noted:

The next challenge was how to communicate the AIF with the patient.

There are myriad ways communication can occur with patients. There was strong consensus that during the initial ED encounter any incidental finding should be verbally conveyed to the patient by the clinician who ordered the study and/or received the report before patient discharge. There was also strong consensus that written communication about the AIF should be included in any discharge paperwork. Ideally, the patient’s primary care physician (if the patient has one) should be made aware of any AIF and should help coordinate follow-up care.

Perhaps the most important area in which agreement was strong was that the communication of incidental findings is ultimately a systems responsibility as opposed to the responsibility of individual clinicians. Although the clinician should make every attempt to appropriately communicate and document the need for follow-up, it is not feasible for an emergency clinician who ordered the test or received the report, nor the radiologist who interpreted and documented the incidental finding, to be responsible for the long-term follow-up of these findings. Although patients bear some responsibility for their health, and ideally primary care physicians will help facilitate follow-up, there are still many who may fall through the cracks, and a systems approach leveraging the electronic medical record and other technology is paramount. There was consensus that best practice in this area includes a follow-up system that assigns a dedicated individual to contact the patient at a later date and track follow-up.

One written template to provide the patient is presented below:

The diagnostic imaging (x-ray, CT or “CAT” scan, MRI, or ultrasound) that was performed during your emergency department visit revealed an “incidental finding”. This is a finding that is not related to your symptoms or complaints and is not definitely abnormal, but in a small number of cases (typically less than 2-5%) may represent a very early cancer. Follow-up is recommended to ensure that it is not cancer, or if it is to allow for early diagnosis and treatment. You should discuss this with your primary care physician and/or follow up in the recommended timeframe.

The third challenge was communication of findings among clinicians. The “consensus” was not strong.

Respondents were close to “neutral” (weighted average, 5.8 of 9) regarding the importance of the radiologist notifying the emergency medicine practitioner (verbally or via text) in addition to the inclusion of the AIF in the report. Average response was slightly higher (6.4 of 9) for the importance of the emergency clinician notifying the primary practitioner about an AIF, and most felt that it was important for the emergency clinician to make the primary care practitioner aware of the findings and need for follow-up via phone call, text, or health record inbox (weighted average, 6.9 of 9; 82% rating 7-9).

For hospitalized patients, respondents felt that inclusion of the AIF in the written report was adequate (weighted average, 6.2 of 9) and that additional communication to the admitting clinician was not as important (weighted average, 4.8 of 9).

The article noted the complexity inherent to bringing in all clinicians who might interact with the patient.

If the patient is admitted, the communication opportunities expand to include an admitting physician, and when the patient is discharged, there is ideally a primary care physician who would be involved in follow-up care. All of these practitioners should theoretically have access to the report that describes the AIF. We sought to develop consensus on best practices for communication among clinicians for AIFs, considering a balance between practicality and assurance of closed-loop communication.

The final challenge addressed follow-up. The consensus was this was a systems problem, and not one that can be shouldered by any individual physician.

Perhaps the most important area in which agreement was strong was that the communication of incidental findings is ultimately a systems responsibility as opposed to the responsibility of individual clinicians. Although the clinician should make every attempt to appropriately communicate and document the need for follow-up, it is not feasible for an emergency clinician who ordered the test or received the report, nor the radiologist who interpreted and documented the incidental finding, to be responsible for the long-term follow-up of these findings. Although patients bear some responsibility for their health, and ideally primary care physicians will help facilitate follow-up, there are still many who may fall through the cracks, and a systems approach leveraging the electronic medical record and other technology is paramount. There was consensus that best practice in this area includes a follow-up system that assigns a dedicated individual to contact the patient at a later date and track follow-up. We did not delve into details of how such a system could be activated or implemented, as there are likely many ways to implement it effectively. Although either a radiologist or an EP could potentially flag reports, approaches that allow automated flagging through structured reporting or natural language processing may provide the most reliable capture.

Although a system such as this does involve investment on the part of the hospital or overall health care system in both automated tracking, communication, and electronic health record infrastructure and personnel, the benefit of identifying malignancies earlier, avoiding the morbidity and mortality of a delayed diagnosis and the resultant litigation, should far outweigh the cost. Likewise, the revenue generated from the follow-up imaging and subsequent care in the system should a malignancy be identified should cover the cost of the program. A recent initiative focused specifically on ED patients with AIFs was able to contact subjects after their visits and/or confirm follow-up in more than 95% of cases6. Other initiatives have been successful focusing specifically on identification of follow-up using electronic health record-embedded tracking processes. 7

In other words, the consensus for managing follow-up was that investments in automated tracking and automated communications could solve the problem, but that was beyond the scope of the paper.

To be clear, “best practices” are not synonymous with the standard of care. And guidelines, while useful, often evolve or at odds with other guidelines.

No doctor wants a patient’s incidental finding to fall through the cracks. Particularly, if that incidental finding is actionable and could lead to early diagnosis/treatment, minimizing morbidity and decreasing mortality.

Still, there is no perfect answer. Some incidental findings are actually benign, but serve as a source of new anxiety coupled with follow-up diagnostic testing which carries its own independent morbidity. Patients will need to learn more about false positives and the risks inherent to deeper diagnostic testing.

Will AI solve some of these problems?

What do you think?

The follow up scan should be ordered prior to the patient’s discharge.

This should be done by the radiology department.

It would be great if there was a functional safety net of primary care physicians that could serve the US is population to follow up on these incidental findings. Unfortunately, in the US a primary care medical is not financially viable. In the US, primary care medical practices can exist only as a loss-leader to capture patients as part of a larger hospital system or in a concierge or cash based model.

What does when do, when the ER physician is also the family physician, and the results are sent to the family physician’s office, stacked up on a desk.

If only circumstances were ideal.

Many patients do not have family physicians and use ERs to provide general medical or urgent care, that could have been handled in a family physician’s office.

Some patients move frequently and don’t have permanent addresses.

Some patients give false contact information because they do not have insurance.

The radiologists can try to contact the ER physicians but that contact is usually about the emergency at hand. Is there a magic solution to this? No. The debate will go on.

Electronically sending records is the best option. Does it mean that the patient will understand or follow up? Will the facility be able to document contact and confirm receipt? Probably not.

Patients will continue to fall through the cracks. Physicians are only human, only have so many hours in a day, and can only do so much in terms of trying to follow up with abnormal results to a patient. I do not see a universal way at present to solve this issue.

In the future when everyone has an implanted chip, they will be able to be contacted.

My Incidentaloma Story

Incidental findings are always a challenge. I had a sudden hearing loss on the L side and because I have an older version of Pacemaker, my ENT doc took a CT scan instead of an MRI. No acoustic neuroma was found, but he thought he saw a midline sulcus cerebral cortical meningioma. And it also looked like that to a very well-qualified specialist, but not the two radiologists who read it. They “saw” expanded, arteriosclerotic vascular changes.

Being over 80, I expect cerebral atherosclerosis. Since I am not an asthenic Tibetan Monk who ate nothing but squash and cabbage since I was 20, that would be what we would see. I cannot get an MRI. Craniotomy is not in my future. False positive? I am a poster child. Maybe. Maybe not. Something is there.

I got some repeat scans over the last 2 years, and the changes were still there, not bigger, but still read by the radiologists as arteriosclerosis. I am stuck with scans. Anyway, these things grow slowly, no matter what they are. I can still play parts of the Rachmaninoff 3rd Piano Concerto (not well) and was able to acquit myself of a detailed consultant report I was hired to do. So, the curtains of my intellect are not yet closed, even though I still sometimes forget what I went into the room to get.

What do you do if you are already old? You accept life as it is, knowing that at least you got a fair deal from God, up to now. More than fair. Very much more.

What do I have to tell you about incidentalomas? They are part of life, and they will always occur as long as we order scans and X-rays looking for stuff. I don’t think you should excoriate yourself, even if you try in vain to contact the owner of the suspect finding. Make an honest attempt to contact and inform. That’s the best you can do.

At least I was able to look at scans with some practice, even though they were out of my specialty. Most of the public can’t even come close to that range of expertise. So, I know what might happen based upon my cortical homunculus (which is mainly sensory). So far it hasn’t, or if it has, I am not aware of it since it is so gradual.

I remain extraordinarily grateful for the life I had no right to expect or demand, including my Incidentaloma.

Michael M. Rosenblatt, DPM